Many books found their place in the corner of my home library during adolescence, young adulthood, and maturity. Fragments of these stories still flicker through my mind sometimes when I try to remember their plots. But there are also some readings I remember with clarity because they raised dozens of questions in my head—some of them unanswered to this day.

Here is my list of a few readings that shaped my understanding of the world. There are certainly more of them, and I am not saying these are the best books you must read. They belong to my past and have earned a place in my heart for their teachings and substance.

Perhaps you could do a similar exercise one day, arranging on paper the titles that stand out in your memory as the most impactful for you. You will discover how revealing of yourself it is.

1. Fabian: The Story of a Moralist by Erich Kästner

Set in Berlin during the last years of the Weimar Republic, the novel follows Jakob Fabian, a disillusioned advertising copywriter who drifts through a city rife with vice, unemployment, and rising extremism.

While he maintains ironic detachment from the decadence around him, Fabian remains committed to his personal ethics. He befriends Labude, an idealistic academic, and falls in love with Cornelia, an aspiring actress willing to compromise herself for success.

Without exaggeration, this is one of the best novels written in Germany’s modern history. The reader closely observes Fabian’s struggle to remain a moral observer while maintaining his irony.

2. The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas

Edmond Dantès, a young and promising sailor, is falsely accused of treason by jealous rivals and imprisoned in the Château d’If. He is stripped of everything he had—including his beautiful fiancée, Mercédès Herrera.

During his years in confinement, he befriends an elderly prisoner who educates him and reveals the location of a hidden treasure. After a daring escape, Dantès claims the treasure on the island of Monte Cristo and reemerges as the wealthy, enigmatic Count of Monte Cristo. Maintaining a low profile, he methodically orchestrates the downfall of those who betrayed him.

In The Count of Monte Cristo, Dumas masterfully portrays the dimensions of betrayal, vengeance, justice, and redemption—and excels in doing so like no other author.

3. The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank

Brought from abroad, my translated copy of Anne Frank’s diary has passed through so many hands I could hardly count them. First—me and my family, then high school teachers, then their students. In the end, it returned to me torn apart, with the pages barely clinging to the cover and full of fingerprints.

Written while Anne Frank and her family were hiding in a secret annex in Amsterdam to escape Nazi persecution, this diary captures the daily life, fears, and dreams of a bright, reflective teenager.

Anne writes candidly about her relationships with her family, her developing sense of self, and her aspirations to become a writer. The diary ends abruptly when the hiding place is betrayed and the occupants are arrested.

Anne and her older sister later died of typhus in a concentration camp. The only surviving member of the family was their father, Otto Frank, who received Anne’s diary from Miep Gies, the family friend who had helped them in hiding.

4. Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë

Brontë’s novel follows Jane Eyre, an orphan raised by a cruel aunt and later sent to a harsh charity school. Despite the obstacles she faces throughout her early years, Jane grows into an independent, intelligent woman.

The uncertainty in her life ceases once she is accepted at Thornfield Hall as a governess for the owner’s daughter. There, she develops feelings for her employer, Mr. Rochester, but she remains steadfast in her moral convictions.

An unprecedented event, however, shatters the peace of the house and compels Jane to leave for an indefinite time, as she finally learns the reason behind Rochester’s sadness.

What strikes me most in the novel is the main character’s development. Seen by many as a story that subtly alludes to feminism and female freedom, Jane Eyre is certainly among those books that showcase complexity and leave their readers deeply stirred.

5. Lust for Life by Irving Stone

This wasn’t an easy read by any means. It left me with mixed feelings and unanswered questions.

Lust for Life is a biographical novel chronicling the life of Vincent van Gogh, from his early struggles as a missionary to his fervent pursuit of painting. The story vividly depicts Van Gogh’s intense relationships with his brother Theo and with fellow artists. While enduring poverty, ridicule, and deteriorating mental health, Van Gogh produces painting after painting without a clear prospect of escaping obscurity.

Irving Stone’s biography of Van Gogh is a remarkable work, exploring the suffering and misunderstood life of an artist. To this day, Van Gogh remains an ambivalent figure, known as the main representative of Post-Impressionism in art.

Although he did not succeed in selling more than one painting during his lifetime, according to most art historians, today Van Gogh’s paintings sell for tens of millions of dollars.

6. Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert

Emma Bovary, the beautiful and restless wife of a country doctor, dreams of passion, luxury, and sophistication—longing for the romance she has read about in novels. Although she is well provided for by her husband and lives a comfortable life, she remains discontent. She embarks on love affairs and indulges in extravagant purchases to escape her provincial reality.

When she can no longer avoid ruin, Emma takes her own life by poisoning herself, leaving her husband and child destitute. Flaubert’s groundbreaking work is a critique of romantic idealism and bourgeois mediocrity.

The themes of moral decay and infidelity are not new and will remain relevant no matter the context. Flaubert published his novel when French society wasn’t ready to speak openly about decadent idealism, and it was met with protest and indignation.

7. Flowers for Algernon by Daniel Keyes

Although this was a novel assigned for a reading club session I never made it to, Flowers for Algernon earned a place in my heart for its originality and uniqueness. Although I am not a big fan of American literature—from my own negligence, not from any lack of quality—this reading is embedded in my memory.

Charlie Gordon, a man with an IQ of 68, is selected for an experimental procedure that has already increased a lab mouse’s intelligence. As Charlie’s intellect soars, he experiences profound changes: he forms new insights, becomes aware of the cruelty he once ignored, and begins complex relationships.

But when Algernon the mouse begins to decline, Charlie realizes his own fate may be the same. The story, told through Charlie’s progress reports, explores themes of identity, human dignity, and the impermanence of knowledge and ability.

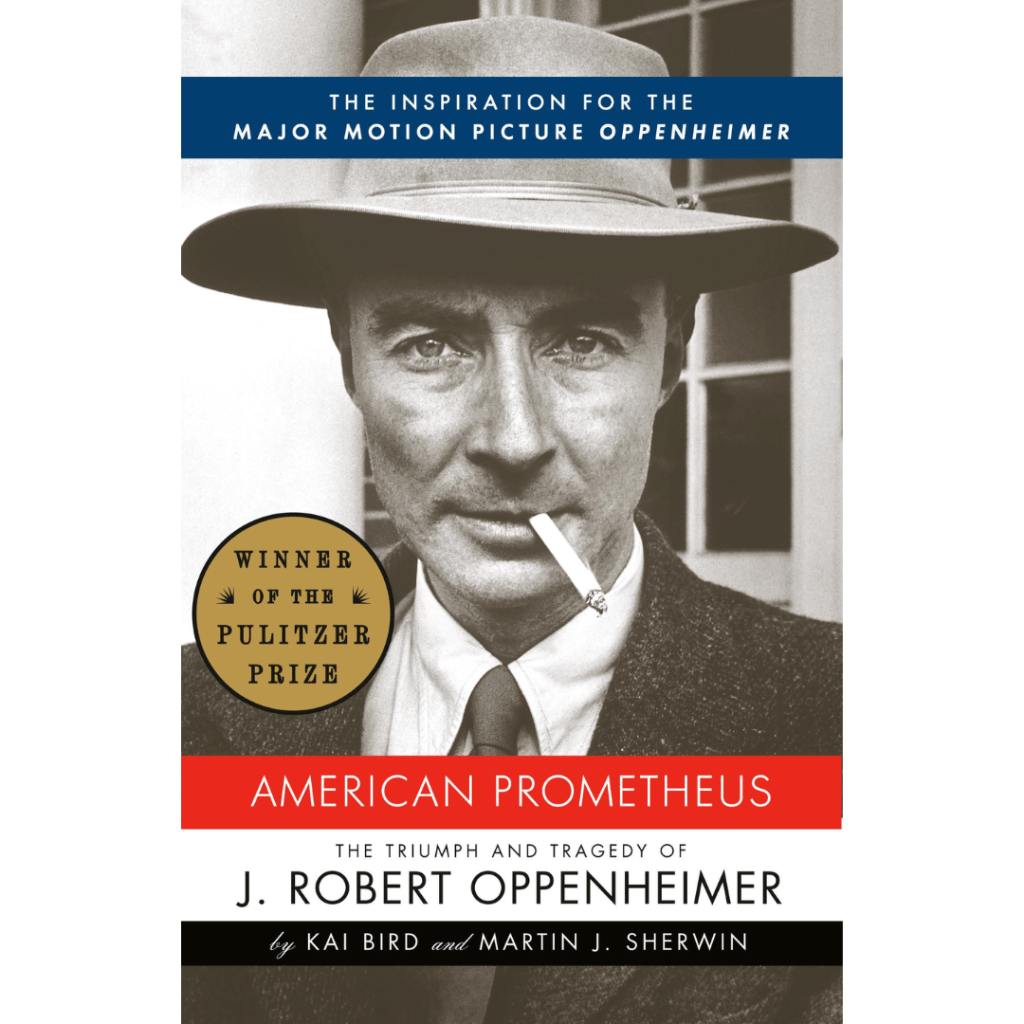

8. American Prometheus: Robert J. Oppenheimer by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin

Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer (2023) earned seven Academy Awards this year, but we shouldn’t forget the remarkable book that inspired the film.

Published in 2005, American Prometheus chronicles the life of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the enigmatic physicist who led the Manhattan Project during World War II.

A particularly poignant chapter of the book explores the 1954 security clearance hearings, where Oppenheimer’s loyalty to the United States was questioned amid Cold War paranoia. He became a target of suspicion due to his associations with left-leaning intellectuals and his opposition to developing the hydrogen bomb.

“Oppenheimer’s warnings were ignored – and ultimately he was silenced. Like that rebellious Greek god Prometheus – who stole fire from Zeus and bestowed it upon humankind, Oppenheimer gave us atomic fire. But then, when he tried to control it, when he sought to make us aware of its terrible dangers, the powers-that-be, like Zeus, rose up in anger to punish him.”

9. Man’s Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl

Psychiatrist Viktor Frankl recounts his experiences as a prisoner in Nazi concentration camps and how he discovered that finding meaning in suffering was crucial for psychological survival. Through his observations and personal story, he develops logotherapy, a form of psychotherapy based on the idea that the will to meaning is the primary human drive.

A man who escaped death on the day of liberation—though it did not spare his family—found a way to cope with trauma and loss while preserving his human dignity and sense of self.

The book is divided into two parts, with a poignant section dedicated to Dr. Frankl’s harrowing experience in the camps. His work has become a game-changer in psychotherapy today, focusing primarily on the search for meaning.

Above all, what strikes me most is how he anticipated many of the problems we face in the 21st century—mainly those caused by boredom and dopamine intoxication.

In his book, he famously quotes Nietzsche several times, particularly—

“He who has a why can bear almost any how.”

Image credits: Pixabay

Leave a comment